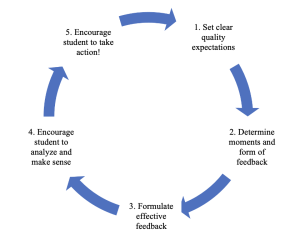

How to provide effective Feedback

|

In the article “How do we look at feedback?” you could read about views on feedback and the importance of feedback literacy. How do you implement a feedback process that helps students develop this knowledge, skills and attitude? The TLC FGw has designed a process for providing feedback based on recent research. Resources

|

|

Students know what they are working toward and what is expected of them.

Formulate concrete and specific assessment criteria

Create a clear assignment description with clear assessment criteria and encourage students to review it from the beginning.

Work with examples

Examples help flesh out often abstract assessment criteria. If you share one “good example,” students will be inclined to make their assignment similar. This can be done in other ways:

For students with little assignment experience:

- Provide some (anonymised) examples where there are strengths and weaknesses among them. Have students rank these from strong to weak, and deduce success criteria for themselves.

- Give some (anonymised) examples and ask students to put the evaluation criteria alongside them. To what extent do the examples meet these and why?

For students with more experience on the assignment:

- Ask students to find a good example themselves and bring it to class. What success criteria did they “use” to select this example?

Feedback at the right moment

Within your tutoring program or course, consider when it is most valuable to the learning process to give feedback. As instructors, we tend to give extensive feedback on final products, however, this is not always effective. Many students barely look at it, and the likelihood that they will incorporate it into a follow-up assignment is low. During grading, limit yourself to justifying a grade and provide feedback during the course or tutorial so that students can actively engage with it. In doing so, alternate different forms of feedback.

Forms of Feedback

1. Collective feedback

Collective feedback is effective and efficient; students often make the same mistakes. However, students are inclined to think that this feedback does not apply to their own work. Therefore, always give an assignment for reflection after the group feedback, such as:

- Describe per comment how it relates to your assignment, what do you recognise, what not and how can you improve the assignment? Students can collaborate on this if necessary.

2. Self-evaluation

Ask students to first assess themselves using the assessment criteria before you do this as a teacher.

- The student first evaluates themself and then selects three assessment criteria on which they would like to receive feedback from the teacher/fellow student.

3. Peerreviewing/peerfeedback

Students can also give each other feedback, in pairs, threes or other combinations. This can save time, but don‘t forget that properly instructing students also takes time.

4. Individual feedback

Of course you can also give feedback 1-on-1, but it is the most time intensive form of feedback.

Written versus audio

You can also provide feedback via audio recordings. Some teachers find this saves time. Students often find it valuable: they hear better where the nuances lie and what the most important points are. Audio feedback often sounds friendlier and more motivating than it looks written. You can easily record feedback for an assignment via Canvas.

Responsibility falls to the student

How do you encourage the student to take more responsibility during the feedback process? You can ask the student to ask feedback questions or select certain criteria on which you provide feedback. De Kleijn (2022) has formulated several questions that can help students formulate ‘good‘ feedback questions for the questions that students ask most often; “I’m stuck, what should I do?”, “Is it good enough?” or “What could be improved?”. View the poster below with examples of questions that students can use to progress if they get stuck (de Kleijn, 2022):

|

Communication about feedback

Once you have decided on the forms of feedback you will use and when you will deliver them, the next step is to communicate very clearly about this format. Discuss the purpose of the feedback you’re giving, and the responsibilities that the teacher and students have in the feedback process.

Share the decisions you make with the students: explain how, in what form and when they can expect feedback during the course/supervision. Pay particular attention to the why question. Students often do not (yet) realise that collective feedback or peer feedback are also beneficial, only recognising teacher feedback as effective.

What can you focus your feedback on? (Hattie & Timperley, 2007)

Hattie en Timperley (2007) distinguish the following four levels of feedback:

a. Task feedback

How well did you understand the assignment? What is the purpose of the task? Focus on the result.

“You have to put in more…”

“Your references do not meet APA standards”

b. Process feedback

How was the result achieved, what approaches/strategies were used?

“This would work better if you had used the strategy from the lecture…”

“How are these dots connected?”

c. Self-regulation feedback

How does the student regulate their own learning process? Self-confidence, self-evaluation, etc.

“You know the characteristics of the structure of a paragraph. Check for yourself whether you have used this.” “Look for the core of this theory, does it match your description?”

d. Feedback on the persoon

Focuses on the person. “You worked hard”

According to Hattie and Timperley, feedback is most effective when it is targeted at the right level. Ideally, your feedback will focus on a combination of the first three levels, with research showing that process and self-regulation feedback are the most effective. The last level, feedback on the person, is the least effective form of feedback.

What constitutes effective feedback? (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2014)

Understandable: use clear and concrete language.

Selective: focus on 2 or 3 things that the student really needs to pick up.

Specific: Point out examples in the work to which the feedback applies. If you ask a question, which can be very effective, also describe why you are asking this question.

Timely: provide feedback at a time when the student can still process it (just-in-time) and thus have the opportunity to practice. This does not mean at the end of a course/track.

Quality-oriented: indicate how the feedback relates to the learning objectives and assessment criteria.

Non-judgmental: provide descriptive rather than judgmental feedback and link this to the learning objectives (and therefore the assessment criteria) of the course. What contributes to this is describing a reader’s perspective: ‘as a reader I would now expect to read this…’, instead of ‘the order of this is illogical’…

Balanced: point out the positive (‘do more of this’) and points for improvement.

Feedback in the document or an assessment form?

By placing feedback in a separate form (rubric or form with criteria) you ensure that you only provide feedback on assessment criteria and you prevent the natural tendency to correct details (such as language errors). The student must investigate for themselves which part of the text the feedback refers to, which is often more effective. Younger year students may benefit more from feedback within the document.

Allow space for an emotional response

It can be difficult and confrontational to receive feedback. Recognise this and give the students space to reflect on this.

- Reflection assignment: As students receive their feedback, ask them to answer the following questions:

- What is your first emotional response?

- What is your first rational reaction?

Analyse feedback

Encourage students to first critically analyse the feedback received about the assessment as a whole, rather than starting with the small points which is much less effective. Ask students to start with the:

- main points about the common thread, coherence, etc.;

- then paragraph-level comments;

- finally, comments at detailed level such as APA and language.

Encourage students to analyse both critical and positive comments: it is also important to analyse why certain feedback is positive.

Feedback dialogue

During the analysis, the student probably had questions. These questions can be central to a dialogue about the feedback. The feedback dialogue can take place between you and the student, or between the students themselves in the form of peer feedback. It helps to pay attention to ‘good‘ feedback questions; It is not enough for a student to just say ‘I don’t understand‘ or ‘is this okay?’. In preparation, ask students to analyse your comments and formulate questions. This way you prevent the dialogue from becoming superficial: the student must adopt an active attitude and take responsibility.

- It can also help to provide the feedback in, or with the rubric. In an adjacent column, students can then indicate per criterion which questions and/or action(s) they have about the specific areas of the rubric.

Always encourage students to actively process the feedback, to avoid the time you invested in providing this support going to waste. This can be done in various ways:

- Action plan: assign students to create a concrete action plan. In what order do they process their feedback and how do they action this feedback? When do they want to tackle this?

- Critical notes: in a later or final version, ask explicitly how the received feedback has been processed and to describe this in ‘critical notes’ (a short description on an extra A4, as the first page).

- Ask the student to describe which 2/3 comments they really picked up from the previous feedback round and how you as a teacher can recognise this. You can also ask which ones they have not processed and why.

- During a resit, you can ask the student to describe (or shade) how and where the feedback was processed for each insufficient criterion.