The Future Societies Lab: getting to work on sustainability issues of social organisations

With financial support from the TLC and IIS Sustainability grant, UvA educator and programme director Dr. Mendel Giezen developed the Future Societies Lab. A course in which students work on research questions on sustainability from society clients. A win-win for different parties for the benefit of societal sustainability transformations.

Course with a win-win on several fronts

“With this, you achieve multiple goals. By working for ‘clients’, students apply their research skills as well as gain practical experience through practice-based research for clients. We think this is important because this is the kind of research students are likely to do after their studies. The course is designed as a win-win on several fronts. It is valuable not only for the students, but also for the social partners and the community service learning ambition of the UvA. In addition, the course strives to make a valuable contribution to societal sustainability transformations.”

“To foster that intensive collaboration, we introduce the SCRUM method and Design Thinking method in training sessions. There are also brainstorming sessions with stakeholders on their issues. But also, weekly update meetings with the supervisor. Finally, the students give a concluding presentation during the presentation day for the external actors or ‘customers’.”

“Thanks to the pressure cooker model, students get different types of insight and gain multiple experiences and skills:

- They gain experience in practice-based research.

- Students develop skills to consult and advise.

- They also develop the ability to translate abstract academic knowledge into concrete situations.

- They gain experience in implementing an applied research cycle.

- The students also learn to present their findings to their ‘client’.”

Clients in the Future Societies Lab

“In the Future Societies Lab, students have so far worked on issues from the clients Gemeente Amsterdam, Waternet, Museum het Schip and various voluntary organisations. This year, the Tolhuistuin and De Gezonde Stad have been added. A nice list of clients, but we are looking for even more partners.”

Request from Museum het Schip about a sustainability garden

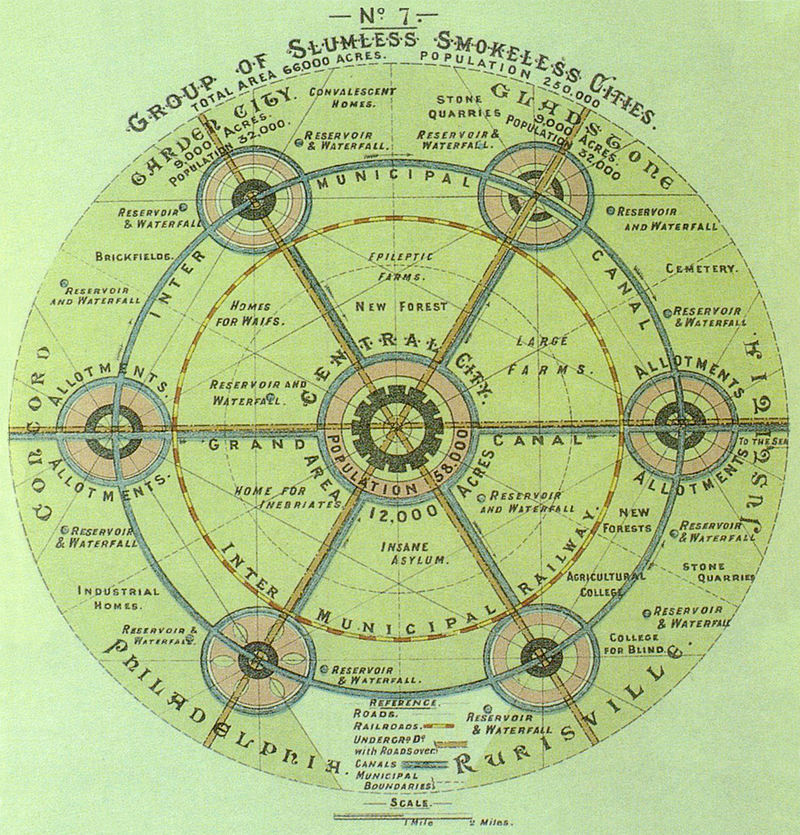

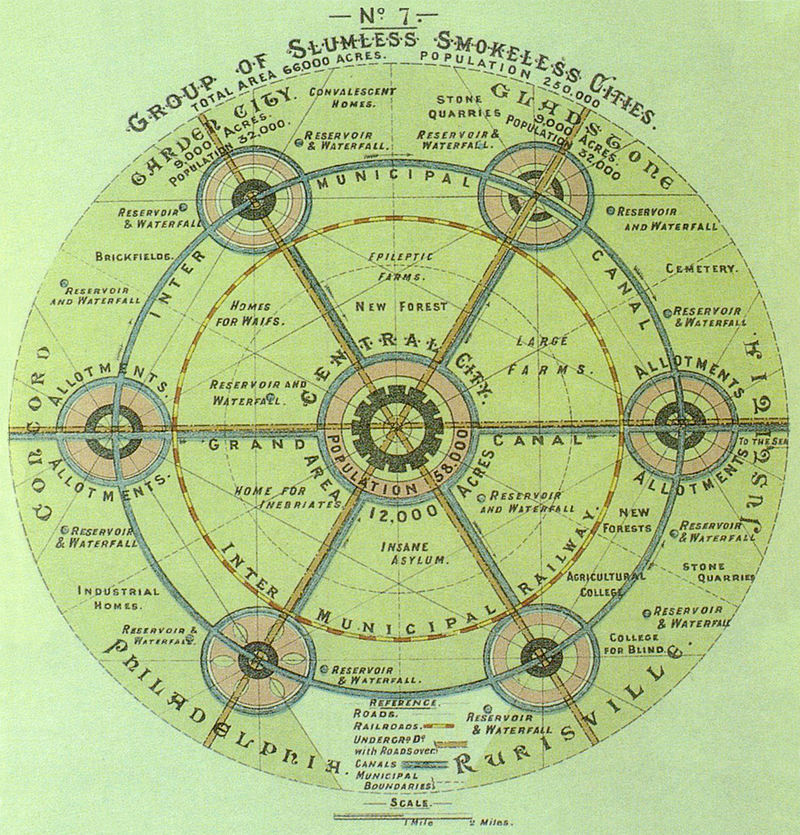

“For Museum het Schip last year, we considered a sustainability garden based on the ideas of the Garden City movement from 1890. As cities became more crowded, there was then a greater need for greenery in the city. So in 1924, a major world planning urbanism conference took place in Amsterdam at the Oudemanhuispoort. After this, the first so-called ‘garden cities’-neighbourhoods and communal inner gardens in the city emerged.”

“The museum’s issue was: how can you actualise that movement from then to now? How do you apply the Garden City principles and how do they contribute to sustainability? The final presentation of this project took place at the museum. In doing so, the museum also organised an exhibition: ‘100 Years of Garden Cities, Garden Cities of the Future and the Past‘, partly based on our students’ research. The exhibition itself was also followed by a conference on the subject. The students’ report was even on the website of Museum het Schip and on the conference website last year.”

Issue for Gemeente Amsterdam: too much brick and not enough greenery

“For the Gemeente Amsterdam, students conducted research into the possibilities in certain neighbourhoods for socially just climate adaptation interventions. For example, needed in case of flooding due to heavy rainfall. The research focused on three so-called ‘development neighbourhoods‘: Venserpolder (South-East), Volewijk (North) and the Lodewijk van Dijssel neighbourhood (New West). Students moved into the neighbourhoods, observed the locations and talked to residents. Based on all this input, the students drew up neighbourhood plans and presented them to the municipality. The municipality then used these plans in turn to draw up their final plan.”

“Venserpolder has certain ‘problem areas’ where the streets have too little greenery and too much stone. This is a problem because stone heats up quickly, creating a ‘heat island’. As a result, in a stone environment it can easily be 5 to 10 degrees Celsius warmer than in a greener environment. In addition, rainwater does not sink well into the ground in such a stone environment. For Venserpolder, therefore, the students designed streets with more greenery, because trees and greenery help combat heat and global warming. They researched which plants and trees could best be used for this purpose.”

“For the Lodewijk van Dijssel neighbourhood, the main focus was on more and safer playgrounds. To this end, students designed green playgrounds in combination with wadis. These are trenches or narrow, shallow channels in the ground that can collect and drain water in case of flooding due to rain. Betondorp, for example, already has wadis.

The Sustainability grant as a boost

“I had been walking around with the idea of creating a lab that connects student projects with questions from practice or society for some time. The UvA foundation Amsterdam Green Campus is doing something similar. I wanted to create a learning element for students based on questions from practice. Thereby as part of the curriculum of the Masters in Planning and Social Geography, so that the type of assignments is tailored to the programme. The Sustainability grant gave me an extra boost and encouraged me to develop the idea I was walking around with. Within a year, this has grown into a valuable subject with a place in a curriculum.”

In a few (non-obligatory) interim meetings, I was also able to share the progress of my project with other grant holders. I also found it interesting and valuable to see what others are working on. We thus created our own ‘network’ that offers opportunities for the future. For example, a project of one of them might be included in the minor Rethinking Sustainable Societies. This is a minor I set up and coordinate and within which I also set up another lab, the Urban Lab.

In doing so, the Sustainability grant brought me 80 hours that could be used to develop the idea. These hours were divided between me and a junior lecturer and came on top of our other work. The money from the fair ended up with the programme, making room in the budget for development of this pilot subject and paying the necessary teachers. In the second year the subject was taught, the costs were already included in the programme’s budget.”