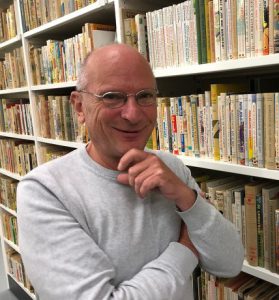

Teacher Story: Paul Dijstelberge

Grassroots project Paul Dijstelberge:

Putting Creative City of Amsterdam (1520-1800) on the (digital) map

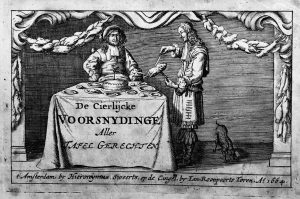

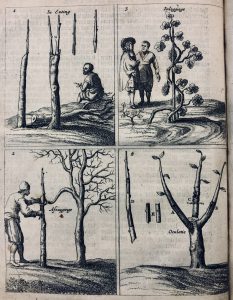

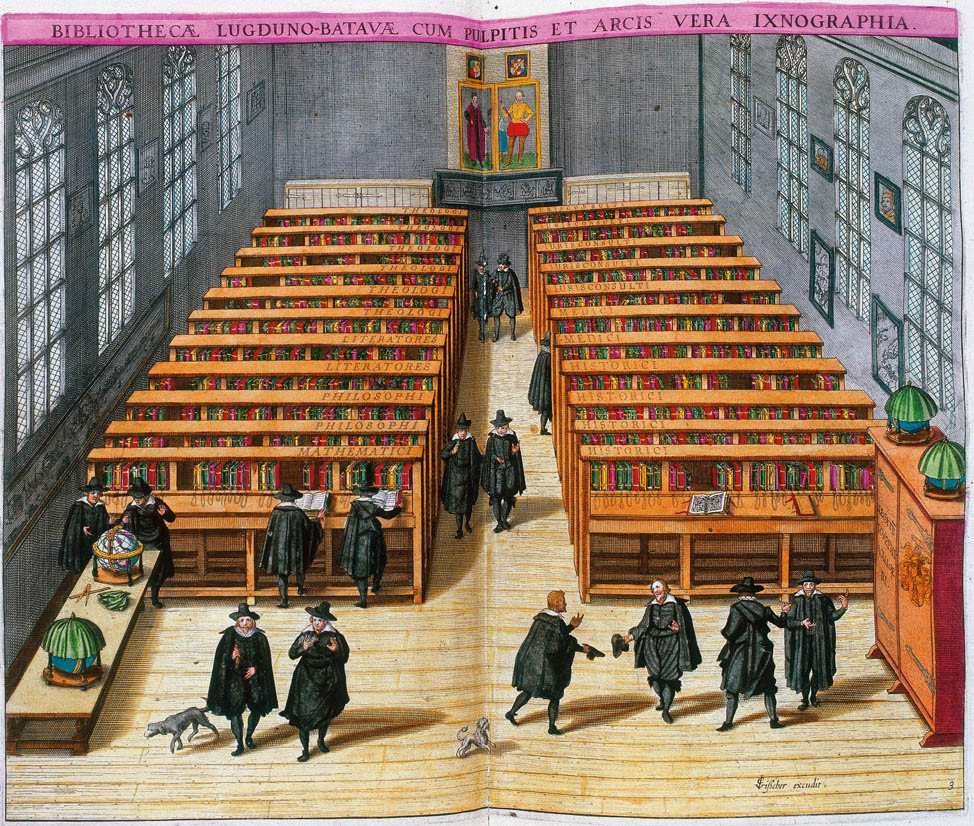

Together with his students and an ICT computer scientist, University Lecturer in Book Studies and curator Paul Dijstelberge has put the Creative City of Amsterdam (1520-1800) on the (digital) map within the space of one year. He was able to do so with the help of a Grassroots grant. The Creative City of Amsterdam is an appealing project in which the world of the book, of printers and publishers is linked to blog texts featuring images of the city, out-of-town residences and of art. These are provided with metadata and geographical references as well as a timeline that allows you to observe changes over the years.

Creative City of Amsterdam (1520-1800) tangible and alive

“The idea for this project actually arose a long time ago when I collaborated on the picture editing for an exhibition at the Allard Pierson Museum and the accompanying book, which happened to be a travel guide of 17th century Amsterdam, written by Emma Los and Maarten Hell. This travel guide, ‘Amsterdam voor vijf duiten per dag’ (Amsterdam for five ducats a day), really appealed to the imagination, with detailed, original information and images of hotspots and places-to-be as you would expect to find in a Lonely Planet, but pertaining to Amsterdam in the 17th century. I thought it would be fun to produce something similar for book printing in Amsterdam in the 17th century, when it was a bustling book town renowned all over the world.”

“This topic gradually expanded to include almost three centuries of Creative City of Amsterdam, because the creative sector was of major economic and global importance at the time. I chose a digital map of Amsterdam to visualize this and make it come to life for everyone, not just the “in-crowd” who know their way around the archives. In a sense what also makes it tangible is that the map shows you exactly where something took place, these locations in Amsterdam often still exist and will be familiar to many people.”

“Each clickable marker on the digital map is linked to a Wikipedia-like page, where you can find a brief overview of basic information about the bookseller, printer or publisher that was located there. That Wiki page then links to blog texts on a digital museum web page, where we provide more detailed information into the subjects, supplemented with visual materials. The three sites are interlinked in such a way that a change in one is also automatically updated in the other two. We now have over 2500 markers and 100 texts. Placing the markers is notably faster than writing.”

Collaboration with students

These three cohesive digital sites consist of scientific work by Dijstelberge himself and by his students. In this way, students have the opportunity to gain work experience and research experience during their studies, which Dijstelberge considers of enormous importance. “For students, this project also means building a public resume. They have something tangible to show to future employers, but also to proud family members and friends, which is an extra incentive to work on the project.”

Infinite Project

“This digital map is a living thing that is constantly being fed with new information. When I announced the project to the world via Twitter that tweet got 120,000 views on the first day and I get a lot of reactions worldwide, including from independent scholars and external researchers as well as from book collectors. Some would like to contribute, which is now happening, thus making the project broader than our university. I manage the map, do the editing and give feedback to the contributors. If they submit something that can contribute it is placed on the map. The whole project is very accessible actually, also in terms of the technical knowledge required to publish something. All we ask for is a Word document. The unique thing is that the map is automatically populated from a spreadsheet and therefore does not need to be filled and changed manually. It’s quite a bit of work for me, but I enjoy it and consider it worthwhile.”

Grassroots grant

Paul Dijstelberge applied for the Grassroots grant at the early days of Covid-19 and completed the project within a year, almost entirely through online contacts. “Projects like Grassroots are important to me, and I’m really glad that this opportunity exists. You are invited to think outside of the box and experiment with fun and innovative projects, whereas I think working within systems like Canvas, for example, means you stay increasingly on those safe well-trodden paths as a teacher.”

With the money from the Grassroots grant, Dijstelberge paid the programmer who gave digital life to his idea. “This computer scientist is a former student of mine. The advantage is that he is both a book scholar and a brilliant programmer. He made the idea that was in my head possible and made it even better than I could have imagined. Once he had built the map, I could independently start populating the online platform with content, together with the students. The main advantage is that the program hardly needs any technical maintenance. About 60 texts/blogs have now been published for the digital museum.”

If you have become curious about Dijstelberge's work, check out the links below

The digital map: Bookhistory.typograaf.com

The wiki page: bookdesign.blot.im

The blogs (in Dutch) – De Vitrine, Digitaal museum voor wetenschap en cultuur: boekwetenschap.org

Additional projects that Paul Dijstelberge is involved in:

Armorica (in Dutch) is a student-run publisher of works produced in relation to the Books Studies master programme of the University of Amsterdam. This includes master theses and dissertations as well as other works relating to the field of Book Studies.

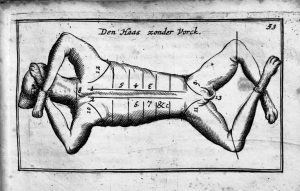

Metabotnik is a website that allows you to create large zoomable overviews from a number of smaller images relating to the same subject. Subjects may vary from images of historical letters and fonts to anatomical illustrations from early medical texts to pictures of people reading, and so on. The website allows people to independently create their own zoomable overviews.